Hacking AI Systems

NIST just released a comprehensive taxonomy of adversarial machine learning attacks and countermeasures. This paper is a treasure trove of info on how attackers can manipulate AI systems, especially those using machine learning.

Midjourney 6.1 The world as a GPU

NIST just released a comprehensive taxonomy of adversarial machine learning attacks and countermeasures. https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/ai/NIST.AI.100-2e2025.pdf This paper is a treasure trove of info on how attackers can manipulate AI systems, especially those using machine learning.

I. Predictive AI (PredAI) Attacks:

Evasion Attacks:

White-Box: Attacker has full knowledge of the model (architecture, parameters, training data). They craft adversarial examples by solving optimization problems, often using gradient-based methods like FGSM or PGD.

Black-Box: Attacker has limited or no knowledge of the model. They rely on querying the model and observing its outputs. Techniques include zeroth-order optimization, decision-based attacks (like Boundary Attack), and transferability (crafting attacks on a similar model and hoping they transfer).

Real-World Examples: Attacks on face recognition systems (using masks, deepfakes) , phishing webpage detectors (image manipulation) , and malware classifiers (modifying files to evade detection) .

Poisoning Attacks: Availability Poisoning: Attacker aims to degrade the model's overall performance, making it unusable. Techniques include label flipping, injecting noise into training data, and exploiting vulnerabilities in retraining processes.

Targeted Poisoning: Attacker aims to misclassify specific samples. They often use clean-label attacks, modifying training data without changing labels, and leveraging techniques like influence functions.

Backdoor Poisoning: Attacker inserts a "backdoor" pattern into the model, causing it to misclassify inputs containing that pattern. Requires control over both training and testing data.

Model Poisoning: Attacker directly modifies the model parameters, often in federated learning settings where malicious clients send poisoned updates. Can lead to both availability and integrity violations.

Privacy Attacks:

Data Reconstruction: Attacker tries to reconstruct sensitive training data from the model's outputs or parameters. Techniques include model inversion and exploiting implicit bias in neural networks.

Membership Inference: Attacker determines whether a specific data point was used in training. They often use shadow models or analyze the model's confidence scores.

Property Inference: Attacker learns global properties of the training data distribution (e.g., fraction of samples with a certain attribute).

Model Extraction: Attacker tries to steal the model's architecture and parameters. This is computationally challenging but can enable more powerful attacks if successful.

II. Generative AI (GenAI) Attacks:

Direct Prompting Attacks:

Jailbreaking: Attacker circumvents safety restrictions placed on the model's outputs, often using techniques like prompt injection, mismatched generalization (exploiting inputs outside the safety training distribution), and competing objectives (playing into the model's drive to follow instructions).

Information Extraction: Attacker extracts sensitive information from the model, including training data, system prompts, or even the model's architecture and parameters. Techniques include exploiting memorization tendencies and prompt extraction.

Indirect Prompt Injection Attacks:

Attacker manipulates external resources that the GenAI model interacts with, injecting malicious prompts indirectly. This can lead to availability attacks (disrupting the model's functionality) , integrity attacks (causing the model to generate untrustworthy content) , and privacy attacks (leaking sensitive information) .

Supply Chain Attacks: Attacker poisons pre-trained models or data used by others, potentially injecting backdoors or other vulnerabilities that persist even after fine-tuning.

Mitigations: The publication also discusses various mitigation techniques but emphasizes that it's an ongoing battle. Defences often involve a combination of:

Robust Training: Techniques like adversarial training and randomized smoothing.

Data Sanitization: Removing poisoned samples from the training data.

Model Inspection and Sanitization: Analysing and repairing poisoned models.

Differential Privacy: Adding noise to training data to protect individual privacy.

System-Level Defences: Limiting user queries, detecting suspicious activity, and designing systems with the assumption that models can be compromised.

Key Takeaways:

AML is a serious threat: As AI becomes more prevalent, so will the risks of adversarial attacks.

Defence is a multi-faceted challenge: We need to combine robust training, data sanitization, model inspection, and system-level defenses.

Stay vigilant and informed: AML is a rapidly evolving field, so keep up with the latest research and best practices.

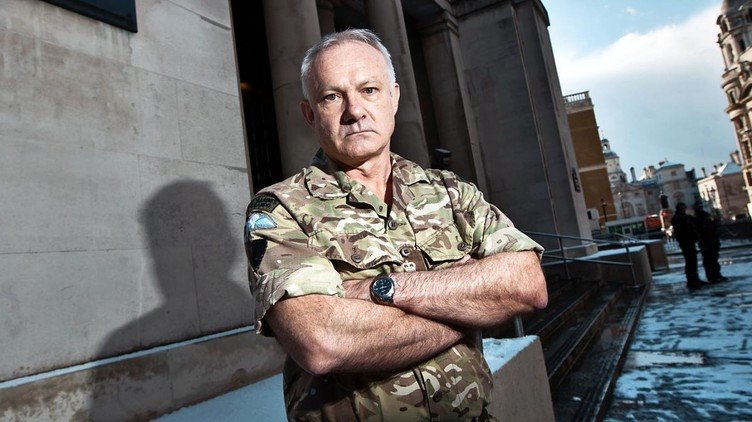

The launch of AI as a Global Strategic Weapon

In 2025, AI will be recognised as a strategic weapon alongside cyber warfare. The development of AI capabilities has progressed in half the time it took to transform cyber capabilities into practical military tools. This rapid advancement means military leaders must quickly enhance their understanding of AI before it is used against them.

Midjourney v6.1 The world as an AI GPU

Entering the year of w-AI-rfare and the snake

In 2025, AI will be recognised as a strategic weapon alongside cyber warfare. The development of AI capabilities has progressed in half the time it took to transform cyber capabilities into practical military tools. This rapid advancement means military leaders must quickly enhance their understanding of AI before it is used against them.

The popular view of weaponised AI is Terminator robots, evil supercomputers, or new super-lethal drones. These are all possible but tactical in nature. AI is now strategic, and in January 2025, we witnessed three significant deployments of AI as a weapon of strategic power.

President Biden conducted the first strike on 13 January, restricting access to GPUs, the core component for training and deploying AI capabilities[1]. The restrictions are complex but aimed at crippling adversaries developing AI and bolstering the US leadership in this field.

Controlling Global Compute and Processing

Core components of the announcement restrict global hyperscalers like Microsoft, AWS, or Google in terms of how many AI data centres they can deploy outside the US. They must now put 50% of their global compute capability into the US. Second, 18 allies were granted permission to purchase GPUs for large-scale data centres in their countries. These countries included the United Kingdom, Holland, and Belgium but excluded NATO allies like Poland. Excluded countries, adversaries or allies would be massively restricted or prevented from acquiring the necessary computing capability to develop or significantly deploy AI capabilities.

This first strategic move sought to maintain the US's global dominance in AI development and deployments. It followed two previous sanctions lists in 2024 that targeted China specifically, although more on China’s response later.

The second strategic launch of AI was made by new President Trump on 22 January, with the announcement of at least $500bn investment in AI under the name project Stargate[2]. This investment is led by Japanese giant Softbank, ChatGPT Creator OpenAI, cloud giants Oracle and Microsoft, and NVIDIA, which supplies its processors.

Investment double the size of the Apollo Programme

In terms of cash investment and adjusting for inflation, this sum is almost double the Apollo Space Programme in real terms. It includes $100bn to construct an AI supercomputer for accelerating artificial general intelligence, the AI holy grail that outperforms humans in thinking[3].

It is an incredible financial investment that no other country can approach, all focussed on true technology world leaders. The outcome was also straightforward: secure American leadership in AI.

In comparison, the UK AI Opportunities Action Plan[4], launched the week before, committed £14bn ($US17.5bn) to AI research and development. This is not an insubstantial sum, but the UK is the fourth largest global investor in AI[5], and the UK plan is over ten years. The US plan is over four years and spends nearly 30 times more.

Combined, these two US policies restricted their allies and tied them to significant US dependency, at least for AI compute capability. The UK Action Plan recognised this constraint: “The UK does not need to own or operate all the compute it will need.” However, the plan also recognises that it will require compute capability that is both Sovereign (owned and operated by the public sector for independent national priorities) and Domestic (UK-based and privately owned and operated). Building that capability will now require US agreement and, probably, US partnerships.

For US adversaries already starved of AI computing capacity, the two US announcements significantly raised the bar in terms of investment that they would need. The announcements created a global shortage of GPUs outside the US, ensured that significant numbers of processors would remain in the US, and probably raised the cost of acquiring GPUs due to the consequent global shortage.

Chinese Economic and Political Counter Moves

At this point, China deployed AI as an economic strategic weapon. DeepSeek AI[6] is a large language model (LLM) and a generative AI like OpenAI ChatGPT. The model itself, R1, posts impressive capabilities on par with the latest public versions from Google and OpenAI in reasoning terms.

Developed in November 2024, public awareness was conveniently timed to coincide with President Trump's inauguration. Public headlines declared China’s Sputnik moment, referencing how the USSR surprised and threatened the US with its first satellite launch.

Launching the model was not a strategic strike. The blow came when it was revealed that the model was trained on a limited number of A100 NVIDIA chips for a rumoured $6m. In comparison, OpenAI trained its latest version on 2,500 A100 chips and spent between $32m and $63 m in training costs[7]. A significant potential saving in terms of cost and energy.

Suddenly, China had an AI capability that could be trained on fewer chips and for 10-20% of the cost. The stock market, especially the US NASDAQ, panicked. In one day, NVIDIA's market value dropped by $600bn, losing 19% in share price, becoming the biggest drop in US stock market history[8]. The NASDAQ Composite Index dropped 3% overall. Softbank, one of the biggest investors in Stargate, dropped 8% in value, wiping all the gains seen since the ambitious project was announced.

A few days later, it became more apparent that DeepSeek R1 was not all it appeared to be. Its training has used massive amounts of OpenAI and Anthropic data and probably used those LLMs to improve and refine its capabilities. It is also true that technological advances make new deployments easier. In this case, China developed an equivalent capability almost 12 months after the first US equivalent version was released and trained it using those US models. This would naturally cost less computing than training a new model from scratch.

However, a simple AI was released to damage US investment and economic confidence in AI. This was a genuinely strategic deployment of a small asset.

The other strategic impact of the DeepSeek R1 announcement was timing. Coincidentally, it was the same week President Trump took office, two weeks after the US announced new restrictions on the sale of GPUs globally, but especially in China, and one week after Stargate launched. DeepSeek announced that it had stockpiled the A100 GPUs needed for its training because of 2022 sanctions limiting their sale to China. In truth, they had to train on limited compute capacity as it was all they could muster together.

The Biden announcement in January makes it even harder for China to acquire these old-generation chips, never mind NVIDIA’s newer H100 units. It introduced restrictions on countries that may have bought large quantities and resold them, possibly ending up in locations that cannot buy them directly. The January announcement makes training harder and almost impossible to deploy next-generation AI without US permission.

Consequently, China announced that it can create competent AI using old chips the same week as the Stargate Project was launched and Trump became President. Trump quickly shared the news with glee, saying it was a wake-up call for US technology[9].

It is highly probable that the strategic deployment of R1 was to shake economic confidence in AI and use political posturing to encourage one person to change policy - President Trump to remove or replace current GPU sanctions. It’s a hard sell, as Trump seems to love tariffs and sanctions, but he also hates losing, so if he thinks sanctions aren’t winning, he may remove them.

China has first Alan Shepard Moment

At the moment, China has caught up with the US on AI. The talks of Sputnik[10] seem to ignore that OpenAI already launched the equivalent of Sputnik in November 2022 with public ChatGPT. If anything, China has finally gotten a rocket into space, but headlines like "China has first Alan Shepard moment" just don't generate clicks.

Yet it is not the weapon of AI that is of interest; it is its strategic deployment. The US has weaponised computational power and access to processors to maintain its economic advantages through AI and, subsequently, the military advantages that AI could bring. In return, China politically and economically deployed AI to damage both confidence and investment, possibly achieving its strategic goals of relaxed processor control.

The rest of 2025 will likely see further strategic uses for AI. The next will be deploying the next generation of large language models, with a probable step change in capability from current versions. Those releases, all coming from US companies, will set a new standard that will be hard to match with models trained on a stockpiled stack of legacy processors.

That release will also prompt China to react and counter differently. It will probably look at exploiting its grip on rare earth minerals, which are essential for the tools and devices that exploit and enable AI. Alternatively, it may increase its economic ownership, where it can, within the AI supply chain.

Yet, twenty days into 2025, on the day China celebrates its new year, it is clear that, like cyber, AI is now both a strategic asset and a weapon.

[1] US tightens its grip on AI chip flows across the globe | Reuters

[2] Announcing The Stargate Project | OpenAI

[3] Sam Altman Wants $7 Trillion - by Scott Alexander

[4] AI Opportunities Action Plan - GOV.UK

[5] https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/ATAG/2024/762285/EPRS_ATA(2024)762285_EN.pdf

[6] What is DeepSeek - and why is everyone talking about it? - BBC News

[7] GPT-4's Leaked Details Shed Light on its Massive Scale and Impressive Architecture | Metaverse Post

[8] What is DeepSeek and why has it caused stock market turmoil?

[9] DeepSeek a 'wake-up call' for US tech sector - Trump

[10] Chinese AI DeepSeek jolts Silicon Valley, giving the AI race its 'Sputnik moment'

The Ethical Landscape of Al in National Security: Insights from GCHQ Pioneering a New National Security Model

This article is part of an impartial series summarising guidance and policy around the safe procurement and adoption of AI for military purposes.

This summary looks at GCHQ's published guidance that is available here: GCHQ | Pioneering a New National Security: The Ethics of Artificial Intelligence

In the rapidly evolving field of artificial intelligence (AI), ethical considerations are paramount, especially regarding national security. GCHQ, the UK's intelligence, cyber, and security agency, has taken significant steps to ensure that their use of AI aligns with ethical standards and respects fundamental rights.

Commitment to Ethical AI

The guidance emphasises GCHQ's commitment to balancing innovation with integrity. This commitment is evident through several initiatives to embed ethical practices within their operations. They recognise that the power of AI brings not only opportunities but also responsibilities. Here are the critical components of their commitment:

Strategic Partnerships: GCHQ collaborates with renowned institutions like the Alan Turing Institute to incorporate world-class research and expert insights into their AI practices. These partnerships ensure AI's latest advancements and ethical considerations inform their approach.

Ethics Counsellor: Established in 2014, the role of the Ethics Counsellor is central to GCHQ's ethical framework. This role involves guiding ethical dilemmas and ensuring that decisions are lawful and morally sound. The Ethics Counsellor helps navigate the complex landscape of modern technology and its implications.

Continuous Learning: GCHQ emphasises the importance of ongoing education and awareness. Providing training and resources on AI ethics to all staff members ensures that ethical considerations are deeply ingrained in GCHQ culture. This commitment to education helps maintain high ethical standards across the organisation.

Legislative Frameworks

Operating within a robust legal framework is fundamental to GCHQ's ethical AI practices. These frameworks provide the necessary guidelines to ensure their activities are lawful, transparent, and respectful of human rights. Here are some of the key legislations that govern their operations:

Intelligence Services Act 1994 defines GCHQ's core functions and establishes the legal basis for their activities. It ensures that operations are conducted within the bounds of the law.

Investigatory Powers Act 2016: This comprehensive legislation controls the use and oversight of investigatory powers. It includes safeguards to protect privacy and ensure that any intrusion is justified and proportionate. This act is central to ensuring that GCHQ's use of AI and data analytics adheres to strict legal standards.

Human Rights Act 1998: GCHQ is committed to upholding the fundamental rights enshrined in this act. It ensures that their operations respect individuals' rights to privacy and freedom from discrimination. This commitment to human rights is a cornerstone of their ethical framework.

Data Protection Act 2018 outlines the principles of data protection and ensures responsible handling of personal data. GCHQ's adherence to this legislation demonstrates its commitment to safeguarding individuals' privacy in AI operations.

Oversight and Transparency

Transparency and accountability are crucial for maintaining public trust in GCHQ's operations. Several independent bodies oversee their activities, ensuring they comply with legal and ethical standards. Here are the critical oversight mechanisms:

Intelligence and Security Committee (ISC): This parliamentary committee provides oversight and holds GCHQ accountable to Parliament. The ISC scrutinises operations to ensure they are conducted in a manner that respects democratic principles.

Investigatory Powers Commissioner's Office (IPCO): IPCO oversees the use of investigatory powers, ensuring they are used lawfully and ethically. Regular audits and inspections by IPCO provide an additional layer of accountability.

Investigatory Powers Tribunal (IPT): The IPT offers individuals a means of redress if they believe they have been subject to unlawful actions by GCHQ. This tribunal ensures a transparent and fair process for addressing grievances.

Information Commissioner's Office (ICO): The ICO ensures compliance with data protection laws and oversees how personal data is used and protected. This oversight is essential for maintaining public confidence in GCHQ's data practices.

Ethical Practices and Innovation

GCHQ's ethical practices are not just about adhering to the law; they involve making morally sound decisions that reflect their core values. Here's how they incorporate ethics into innovation:

AI Ethical Code of Practice: GCHQ has developed an AI Ethical Code of Practice based on best practices around data ethics. This code outlines the standards their software developers are expected to meet and provides guidance on achieving them. It ensures that ethical considerations are embedded in the development and deployment of AI systems.

World-Class Training and Education: Recognising the importance of a well-informed workforce, GCHQ invests in training and education on AI ethics. This includes specialist training for those involved in developing and securing AI systems. By fostering a deep understanding of ethical issues, they ensure their teams can make informed and responsible decisions.

Diverse and Inclusive Teams: GCHQ is committed to building teams that reflect the diversity of the UK. They believe a diverse workforce is better equipped to identify and address ethical issues. By fostering a culture of challenge and encouraging alternative perspectives, they enhance their ability to develop ethical and innovative solutions.

Reinforced AI Governance: GCHQ is reviewing and strengthening its internal governance processes to ensure they apply throughout the entire lifecycle of an AI system. This includes mechanisms for escalating the review of novel or challenging AI applications. Robust governance ensures that ethical considerations are continuously monitored and addressed.

The AI Ethical Code of Practice

One of the cornerstones of GCHQ's guidance to ethical AI is their AI Ethical Code of Practice. This framework ensures that AI development and deployment within the agency adhere to the highest ethical standards. Here's a deeper dive into the key elements of this code:

Principles-Based Approach: The AI Ethical Code of Practice is grounded in core ethical principles such as fairness, transparency, accountability, and empowerment. These principles are the foundation for all AI-related activities, guiding developers and users in making ethically sound decisions.

Documentation and Transparency: To foster transparency, the code requires meticulous documentation of AI systems, including their design, data sources, and decision-making processes. This documentation is crucial for auditing purposes and helps ensure accountability at every stage of the AI lifecycle.

Bias Mitigation Strategies: Recognising the risks of bias in AI, the code outlines specific strategies for identifying and mitigating biases. This includes regular audits of data sets, diverse team involvement in AI projects, and continuous monitoring of AI outputs to detect and correct discriminatory patterns.

Human Oversight: The code emphasises the importance of human oversight in AI operations. While AI can provide valuable insights and augment decision-making, final decisions must involve human judgment. This approach ensures that AI serves as a tool to empower human analysts rather than replace them.

Security and Privacy Safeguards: Given the sensitive nature of GCHQ's work, the code includes stringent security and privacy safeguards. These measures ensure that AI systems are developed and deployed in a manner that protects national security and individual privacy.

Continuous Improvement: The AI Ethical Code of Practice is a living document that evolves with technological advancements and emerging ethical considerations. GCHQ regularly reviews and updates the code to incorporate new best practices and address gaps identified through ongoing monitoring and feedback.

Conclusion

GCHQ's approach to ethical AI in national security expands its commitment to protecting the UK while upholding the highest standards of integrity. Its legislative frameworks, transparent oversight mechanisms, and ethical practices set a high standard for other organisations.

As it continues to respond to technological advancements, GCHQ balances security with respect for fundamental human rights.

This approach ensures that as it harnesses the power of AI, it does so responsibly and ethically to keep the UK safe and secure.

Transformation is Dead. Long Live AI-Powered Transformation

The concept of 'digital transformation' has become diluted. While some industries have been reborn – think finance and technology – others lag, relying on incremental tweaks instead of true disruption. As a leader in defence, I see this firsthand and ask myself, why?

The concept of 'digital transformation' has become diluted. While some industries have been reborn – think finance and technology – others lag, relying on incremental tweaks instead of true disruption. As a leader in defence, I see this firsthand and ask myself, why?

Three Lenses, One Observation

My background offers a unique perspective on this challenge:

The Professional Services View: As a consultant, I've witnessed the transformative potential of technology firsthand. Global businesses embrace digital tools, reshape their core processes, and emerge as dominant forces in their sectors. In many sectors, a worker from the 1990s would struggle to comprehend their modern-day workplaces. Yet, some sectors – notably those with well-established legacy systems and ingrained practices – seem reluctant to adopt a transformative mindset fully. While incremental change occurs, the fundamental structures and ways of operating remain largely the same.

The Geek's View: From my early days working with defence AI projects to being part of Microsoft's revitalisation under Satya Nadella, one thing stands out: Transformation without the right mindset and leadership is an uphill battle. Nadella's focus on a growth mindset revolutionised Microsoft. It empowered people, broke down silos, and instilled a culture of relentless innovation across the entire organisation. This kind of top-down commitment is the secret ingredient often missing from today’s transformative efforts.

The Soldier's View: Since the 1990s, visionaries have painted a compelling picture of future warfare: Digitally enabled, AI-driven, highly networked, fundamentally changing how we operate. Sadly, much of that thinking evolved purely into cyber, then became wrapped into security. The digital promises have not been delivered, even when events like the conflict in Ukraine demonstrate the accuracy of these predictions on a broad scale. Yet the on-the-ground reality within many militaries beyond Ukraine tells a different story. Core doctrines, operational models, and even individual soldier skill sets often have more in common with decades past than they do with the cutting-edge future we envision. This calls into question whether the transformative urgency felt in the tech sector indeed permeates the military the way it needs to. A soldier from the past would likely recognise much of our current operations.

The Old Transformation Model's Achilles Heel

In 2014, forward-thinking defence articles like "Warfare in the Information Age" depicted AI-driven conflict. That vision is now grimly unfolding in Ukraine, underscoring the power of drones, intelligent systems, and network-centric warfare. Yet, within our military organisations, the same transformative fire and burning urgency often seems absent. Could it be that the classic top-down model of cultural transformation isn't the best fit for the military mindset?

The traditional transformation model hinges on sweeping cultural changes led from the top. This approach can be practical but faces challenges within a military environment. It's often slow, and its results can be unpredictable as technology outpaces the speed of cultural adaptation. Military organisations are also traditionally resistant to change with embedded, established cultures.

Meanwhile, the tech sector thrives on a drastically different model. Fuelled by constant competition and the need for relentless innovation, tech leaders evolve at a pace that leaves little room to ponder cultural challenges. Tech companies have short histories and are less inclined to cling to ancient traditions or practices.

“This jarring contrast begs the question: have we fallen behind in the defence sector? Have we clung to a transformation model that may have already reached the limits of its effectiveness?”

It's Time to Deploy AI to Transform, Not the Other Way Around

Here's a radical proposition: use AI as the Transformation Engine. Too often, we envision digital transformation as a cultural prerequisite before deploying new technologies. But what if we flipped the script? AI doesn't just automate tasks; it creates new ways of working, thinking, and collaborating. AI can compensate and adjust for resistance, and by deploying AI tools strategically, we can:

Simplify Complex Processes: Break down bureaucratic barriers and streamline decision-making with AI-powered recommendations and insights.

Address Skill Gaps: AI can provide on-the-job training and support, augmenting human capabilities and levelling the playing field.

Deliver Measurable Results: AI's impact can be quantified, making the benefits of transformation undeniable and building trust in further adoption.

We Have the Tools Today: The AI revolution isn't a distant dream. Across defence, projects are underway that demonstrate the transformative power of AI right now. We see current examples of how AI can deliver transformation, including:

Air Tasking: AI to help plan and execute air control and dominance, accelerating and amplifying air power.

Enhanced Intelligence Analysis: AI helps sift through massive data sets, uncovering patterns and improving situational awareness.

Cybersecurity Optimisation: AI detects anomalies and prioritises threats, strengthening our digital defences.

The key is empowering people and teams with AI tools. It's about demonstrating tangible value, not waiting for some abstract cultural shift to occur magically. Some may complain that we should not use AI to change behaviours or cultures. Yet, it merely accelerates the change that all would agree needs to happen within our military organisations.

The Choice We Face

Path One: Stagnation – We cling to incremental improvements, hoping that a cultural breakthrough will magically appear someday.

Path Two: Revolution – We acknowledge that the traditional transformation model might be obsolete. But instead of despair, we see this as an opportunity. AI empowers a new kind of transformation – driven from the bottom up, results-oriented, and fuelled by the urgency of the present.

We have the expertise, and the technology is here. Are we prepared to shed outdated paradigms and embrace a future-proof military force powered by intelligent transformation?

How to think about military AI, not what to think.

Midjourney prompt: How to think about military AI

I'm an evangelist, someone who passionately believes that they have seen the future. My future belief is that artificial intelligence, automation, machine learning presents an opportunity to enhance human ingenuity far beyond any previous technology.

It also has the potential to cause great harm.

I am sometimes accused as someone who thinks differently, and I am not always sure that is meant as a compliment. Yet it is in this perspective, of a society grappling with major changes and upheaval through automation, that I urge military leaders to consider HOW they think about AI, and to move away from a narrative that is mostly focussed, if at all, on WHAT to think.

What do I mean by this difference? When the US and UK adopted a doctrinal approach to warfare in the 1980s, they adopted an approach that enables soldiers to think about their situations and decisions rather than follow a simple drill or routine. This change was resisted by generations of military officers, shaped by deterring Soviet aggression in Europe, more used to prepared positions with a sequence of triggers and responses than independent action. I experienced this resistance.

We began to encourage leaders to learn how to think about any problem rather than what answer to provide to a specific problem.

Yet technology adoption has been blighted by a preference to deconstruct innovative technology rather than understand the opportunity, especially in the UK.

The impact of the machine gun in 1914 led to the creation of The Machine Gun Corps in 1915. Their role was to understand the technical aspect of machine guns and to deploy them more effectively. Eventually, in 1922, The Machine Gun Corps was disbanded, and its role and purpose embedded intrinsically into infantry brigades. We took seven years to truly integrate this essential weapon.

The pattern was repeated with the tank, where the Heavy Machine Gun Corps owned the technical adoption and maintenance of the tank as mobile machine gun posts. Thinking on how to deploy tanks came later. It is probable that the decision to limit Germany's physical access to armoured vehicles accelerated its thinking on how to deploy tanks in new ways rather than languish in admiring their mechanics.

In both cases, the emphasis was on a specialist group understanding a specialist equipment and eventually implementing that equipment on the battlefield. We deconstructed the system, understood it at a systems level, and eventually became comfortable with the technology over many years before integration.

We are too often continuing this archaic approach with automation and AI. The utility of AI is explored by specialist units and procurement parts of defence, usually innovation or experiment teams, and is seldom experienced by or involves troops struggling with genuine issues. Bolder military elements are attempting to get AI into the hands of users, but their foresight is often hindered by both access to soldiers and support for development.

Like drones and cyber before, the opportunities to explore and experience automation on a general military exercise are few. Automation exercises are designed, established, and run purely to explore the AI system rather than examine its integration and exploitation with other military systems. Large military exercises are conducted without any automation.

This training focus may mean that large troop movements can be conducted smoothly across exercise plains and areas. These exercises may validate that current equipment continues to operate as expected, or that commanders are able to deploy tactical manoeuvres. It avoids training exercise serials and schedules being disrupted by automation.

Yet current exercises are not preparing the next generation of leaders for warfare in the intelligent age.

Leaders and those led, at every level, need to see what is possible with automation and to explore and exceed its limitations. It is only by using an equipment that empowers soldiers to learn about its true utility, and it is only through experience with innovative technologies that their disruptive nature can be explored or developed. Technology elements may not be ready for full deployment, but if commanders are not thinking about how they could use AI, even if theoretically, they will miss the opportunity to shape how they will use AI.

Our soldiers are often disruptive, and military leaders need to fire their enthusiasm for how AI will disrupt their core business.

Today, it is often too easy for a military leader to deny that they have technological understanding unless they are in a technical branch. There remains a certain badge of honour to declare that they know nothing of mobile phones, or do not use applications, or have no time for information technology. Defence appears unique in its desire to spend so much of its budget on technology and so many of its leaders to flout it.

Some remain convinced that basic navigational skills are more useful than GPS or that fitness trumps technology. This misses the fundamental point that future successful military leaders will be both fit and understand technology, they will still understand the traditional and enhance it with technology.

This is the truth behind automation – it enhances human ingenuity and defence is not separate from this disruption.

Military leaders who eschew this automated enhancement will not be championed but be defeated.

Therefore, I propose that:

Current military academies and training centres seek to implement and adopt automated tools and practices in every aspect of training.

We need to encourage current and future leader that understanding and exploiting AI is at the very heart of their thinking about warfare.

I have said before that doctrine needs to be rewritten with automation in every element, questioning how it changes our approach to conflict.

We need to develop insatiable curiosity about the potential of technology within all our military leaders, especially the fighting arms.

We must generate a cohort of leaders who will test and explore the greater potential of technology rather than ignore or abhor it.

Future leaders are curious, not curios. They need our help to foster and fuel their curiosity.

The Future of Warfighting is Today: the strategic case for interoperability within and across nations Pt2

The future of warfighting and interoperability

Midjourney prompt: Modern military helicopter desert

A two-part recommendation that interoperability demands more investment and greater prioritisation from current military and government expenditures. Reviewing the Deloitte Center for Government Insights recommendations of September 2021 in the light of Ukraine and economic uncertainty, we find that today is the right time to increase interoperability within and across the free world. In this second part, we look at the case for investment.

The maturity of Interoperability is not matching maturing of threats.

Our strategy review found that defence departments and ministries are devising to combat today's challenges with other government agencies, nations, and commercial companies. Yet, our interoperability maturity assessments identified that most militaries organisationally struggle to enable the coordination required for today's defence challenges. They simply lack enough time, money, or people within their departments to address various challenges.

Take the U.S. Cyber Command's strategy of "defend forward" to counter grey zone cyber threats, placing U.S. military cyber experts overseas to disrupt attacks headed for the United States. This strategy demands coordination with host nations, military and security agency cyber forces and familiarity with commercial technologies [1]. More profoundly, we highlighted how coordination needs to extend into the temporal dimension rather than mere military domains and that synchronisation of response and decision-making would require significantly increased interoperability maturity [2]. The current patchwork approach to link processes and activities for interoperability adds costs, creates vulnerabilities, exposes capability gaps, and remains rigid to diverse defence challenges.

Interoperability investments now return greater value

Traditional interoperability investments faced two test criteria: increase political legitimacy as part of a larger coalition and improve operational efficiency. The costs of purchasing new common equipment, the time to develop coordinated operations, and the investment to agree shared doctrine had to be less than the value of these two criteria.

Last year, increasing NATO defence expenditure was a political choice made in the context of recovery from a global pandemic. The strategic logic existed but the value did not justify the financial investment. With a ground war in Europe, the investment in NATO is far more apparent today. However, nations seek primarily to invest in national defence industry and capabilities first and still place interoperability second.

This decision is basic economic logic, investing in industry to maintain productivity and national economies. Purchasing new weapons and vehicles and recruiting soldiers has an immediate investment benefit. Yet it does not capitalise on the benefits of interoperability that we identified last year.

Investing in the maturity of interoperability delivers economic and defence benefits.

The need to face a changing global situation with increased interoperability funding is justification alone for investing more. The broader and immediate benefits of doing so make this a compelling case to ignore.

By itself, our third interoperability rule, interoperability today is a strategic advantage, offers significant benefit for investment especially when facing increasingly complex and diverse challenges. Increased interoperability provides the ability to match and flex against threats. At a time of increased conflict and tension, we cannot wait to create a strategic advantage until the last safe moment.

With the realisation of our second rule, no nation can meet today's defence challenges alone, then interoperability investment becomes a clear priority. Investment in interoperability maturity across defence, other national security agencies, government departments, NGOs, and industry will create resilient structures and establish robust relationships to counter known threats and respond to unexpected new ones. This investment requires coordination to avoid every element developing isolated interoperability solutions. Based on our studies, that coordination is justified as each respective entity will also improve its abilities to adapt, modernise, and transform its own core functions from this investment.

Our final rule, interoperability is not new, is the platform on which any effective investment can be made. The research showed that effective interoperability required an existing organisation to focus the investment, an agreement to define its nature, and a platform to enable the investment. Where none of these criteria existed, the maturity was low, and effectiveness was limited. We could see performance improvements where one or more existed. Combining all three accelerated maturity and effectiveness significantly, especially when based on existing structures and relationships.

Interoperability is different from investment in modern technologies or dramatic digital transformation. The allure of the new too often tempts military planners, and militaries may still require these different technology or transformation investments. However, when a choice must be made to ensure the best investment decision, options that support interoperability are more likely to empower transformation than one that merely seeks to pursue new equipment. The nature of interoperability makes it an accelerator for both technology and transformation.

This is also not an argument to invest in traditional forms of interoperability to spend newly increased defence budgets. Purchasing common technologies is a useful step, but defence organisations need to mature beyond their conventional interoperability standards to include other government organisations, private industry and the various politics, policies, and economics that come with broader coordination. Today's challenges may resemble those of the past, but their character is new. Investment in interoperability maturity that enables militaries to operate outside themselves is required.

The future of warfare is today.

Defence has spent the last 20 years responding to challenges while claiming that the current challenge is fundamentally different from any future challenge. They have been countering global terrorism, stabilising and then extracting from failed states, countering threats to the rules-based world order from resurgent peer adversaries and addressing increased grey zone & cyber threats. Each has distracted and diverted funding and prioritisation. Yet every challenge required and benefitted from interoperability investment.

Increasing interoperability investment is now critical. We can no longer delay with European conflict, increased tensions in Asia, growing diversity of cyber threats, and more demanding challenges to the rules-based international order. Interoperability improves our ability to meet these challenges and enhances our collective abilities to adapt to new threats. Our conclusion last year remains the same today: By cultivating interoperability today, defence organisations can be ready for the future, whatever it may bring.

[1] U.S. cyber strategy of persistent engagement & defend forward: implications for the alliance and intelligence collection: Intelligence and National Security: Vol 35, No 3 (tandfonline.com)

The Future of Warfare is Today: The strategic advantage from interoperability within and across nations

The military advantages of greater interoperability

Midjourney prompt: Modern military soldiers

A two-part recommendation that interoperability demands more investment and greater prioritisation from current military and government expenditures. Reviewing the Deloitte Center for Government Insights recommendations of September 2021 in the light of Ukraine and economic uncertainty, we find that today is the right time to increase interoperability within and across the free world. In this first part, we look at the interoperability rules for future warfare.

Last year, The Deloitte Center for Government Insights reviewed twelve countries and sixty representatives to identify ways and insights to improve effectiveness across key military areas. We identified four leading defence challenges across all respondents:

Peer warfare.

Technology-driven grey zone threats.

Limited-scale warfare.

Defending the rules-based international order.

The goal was to generate discussion to improve global initiatives and demonstrate the realisation that more significant aligned activity was essential for intelligence age warfare. The outputs are collated here under Future of Warfighting.

At the time, very few individuals viewed Ukraine and Russia as a potentially imminent conflict [1], most believing that the conflict would continue to be tense rather than hot[2]. Despite the 2014 invasion, it looked likely that Russia would not be bold enough to strike deeper into Ukraine. Behind the scenes, military leaders feared that any Russian aggression would be short and vicious.

Today, Russia's invasion has accelerated the West's need for honesty to recognise, understand, and respond to pressing international interoperability issues and collectively act to meet the identified defence challenges listed above. Ukraine has valiantly resisted Russian aggression with global support and stubborn bravery whilst offering hard, violent proof for the value of interoperability and international cooperation.

The West cannot wait another year, and Ukraine cannot wait any longer.

Our recommendations start with three simple rules. The first is that Interoperability is not new and that most military operations worldwide are multilateral. Militaries value interoperability and, when pushed, will work hard to resolve any issues. Yet there has been little incentive to make interoperability a top priority until now, despite clear examples in recent military history. For instance, the Anglo-French combined expeditionary forces in the Sahel for Operation Barkhane struggled with basic equipment interfaces and more challenging differences in rules of engagement and command philosophy [3].

In Ukraine, interoperability is now a priority where its forces receive Western equipment in limited packets. Its soldiers learn and integrate these items alongside their own tactics and other equipment. We see the strain on supply, logistics, and operational tempo as they learn these lessons in combat.

No nation has enough precision-guided munitions to sustain a protracted peer engagement [4]

Our second rule is that no nation, even the U.S., can meet today's defence challenges alone. Our research across all twelve countries identified stark shortcomings in the supply chain, stockpiles reduced under budgetary controls, and closed production lines that reduced restocking responsiveness. At the other end of the spectrum, we saw that it was clear that no military can, by itself, address the flood of misinformation permeating social media platforms that characterise intelligence age operations.

Success today requires militaries to operate outside themselves, to be interoperable with other nations, other government agencies, and even commercial industries in new ways. Ukraine starkly shows this rule to be valid, with both Russian and Ukrainian militaries struggling to supply their artilleries, replenish depleted munitions, and train or operate with other nations.

All armies are calculating the ammunition and munition expenditure rate in Ukraine and comparing it to their stockpiles and reserves. The comparison is grim, with even significant forces seeing forecast depletion of all munitions measured in days rather than weeks, whilst restocking from suppliers is measured in months rather than days. Hoping to fight differently to avoid this attrition challenge lacks credibility, as the adversary often sets the nature of conflict as much as the home side.

Nations putting in the challenging work now will meet the demands of the future, whatever they may be.

Our third rule is that Interoperability is more than just a political expedient, a way of growing exports, or demonstrating global reach. Interoperability today is a strategic advantage. Interoperability gives militaries more options, greater strategic agility, with the flexibility to adopt and adapt to the flow of conflict with greater confidence.

Consider the view that Russia saw Ukraine's reach toward the West and NATO as a threat because it delivered this strategic advantage. A Ukrainian military with NATO equipment, operating within NATO's cyber security and intelligence reach, and resupplied from across NATO industries would significantly deter any future Russian interference. Greater interoperability between NATO and Ukraine offered a strategic advantage that Russia could not counter. If completed, interoperability would not only make Ukraine resistant to Russian aggression but also confident enough to reclaim the regions seized by Russia in 2014. This proposition is evident in how NATO intelligence, supplies, and equipment bolster Ukrainian effectiveness today.

Interoperability rules are more relevant today than last year.

We reviewed the political, strategic, and doctrinal documents of twelve countries across North America, Europe, and Asia to determine their leading defence challenges. At the time, conversations around peer-on-peer warfare were considered increasingly irrelevant, with the need for broad-spectrum military, political, and economic warfare highly unlikely. Yet all countries showed strong indicators that peer-on-peer conflict remained a key challenge.

This insight went further than soldiers still fighting the last war or purchasing old capabilities from previous conflicts. We identified convincing evidence that all surveyed militaries were adopting innovative technologies, tactics, and toolsets to face new ways of warfare. We also determined successful adoption often occurred when armies implemented these new tools over existing structures rather than merely replacing systems. An infantry brigade could exploit UAV capabilities far quicker than asking a new UAV brigade to operate alongside the infantry one. The infantry brigade may, subsequently, fight in a way unrecognisable to its predecessors, but the core skill set of peer-to-peer conflict seems to underpin successful capability adoption.

Interoperability provides an advantage within as well as across a military force. Our research [5] examined the scale and demands of interoperability across four military functions at five maturity levels, from Level 1 Baseline (able to interoperate with secure systems and trusted data) to Level 5 Systemic (internationally coordinated responses, with automated tooling and shared cultures). We could see that adopting new capabilities was easier for organisations at the higher levels of interoperability and that these same, higher-level organisations could adapt existing structures faster.

This is a crucial lesson as militaries seek to converge across domains and environments and address multi-domain integration to meet current military threats. Interoperability provides a strategic advantage, a force multiplying effect on performance, and enhances adaptability against threats and change. This alone should justify increased investment, yet we are not seeing this reality.

In the second part, we examine this case for more significant interoperability investment.

[1] The West faces a test of unity over Russia as tensions intensify between Moscow and NATO | World News | Sky News

[2] Kremlin says NATO expansion in Ukraine is a 'red line' for Putin | Reuters

[3] https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/industry/public-sector/future-of-warfare.html#endnote-2

[4] https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/industry/public-sector/future-of-warfare.html

[5] https://www2.deloitte.com/global/en/pages/public-sector/articles/future-of-warfighting.html#:~:text=Interoperability%20functions%3A

Wordle as a story of information warfare

Can posts about Wordle teach us more about information warfare?

"Is Wordle getting harder?"

"Wordle sells out."

"What in the world is happening to our beloved Wordle?"

"How Wordle won over the world."

You may have heard of Wordle, where online players attempt to guess a five-letter word correctly in six or fewer tries. It now has millions of daily players and was invented by one person as a simple game for their partner to enjoy.

In late January, The New York Times paid "low seven figures" to own the game, website and code exclusively. The website is vital for the game as there is no separate app or program, and the entire solution to the game is openly available on that single page.

That purchase created a unique learning experience for people interested in how information and data shape our perceptions and reality. Three public conversations started almost immediately after the purchase:

New York Times has changed the game and made it worse /harder/ easier /American/elitist.

The acquisition means people no longer trust the game to be fair or the same.

The players no longer feel that they own the game and that others now own it.

Internet forums and panels have aggressively debated these points. People sought out like-minded thinkers to agree with them and shouted down those who didn't.

Minimally, these conversations reflect more prominent topics and conspiracy theories shared across the internet. It allows us to watch an information narrative develop and evolve within a limited scope.

Crucially, we can watch these stories develop with a fixed baseline of knowledge.

Here is why this story is a great reference point: nothing has actually changed in the game, it is all narrative and stories

The website contains all of the answers and underlying code, and it always has. The core data and game is still the same and openly available.*

Therefore, we can see if anything changes in the code and compare physical change with perceived difference.

Currently, it's all perception and story rather than truth.

Since the acquisition, the New York Times has removed a handful of potentially offensive words, but the answers for each day remain the same and stay in the same order. Previously "Boozy" followed "Dozen", and at a specific point in the future, "S*a*e" will follow "R*r*l" (I'm trying to avoid spoilers for the answers in 2026).

So, if nothing has changed, why is this critical for information warfare? Why are people so excited and angry if it's still all the same?

The Wordle case shows us how narrative shapes and reinforces our opinions rather than data.

People are always quick to blame anything else rather than their performance; that is usually human nature. Rather than having a poor day, we generate new narratives to blame factors outside our control. Whether it was not wearing a lucky item, the change in weather, or a sinister organisation, we tell ourselves that we are not at fault.

Our online lives make it simpler to accuse these outside influences and find other people who share our perspectives. These groups then reinforce our belief, becoming the oft-quoted "online echo chamber".

We can see these echo chambers form online around Wordle topics. Reddit communities have multiple threads about how Wordle changed, how to protest for the changes to be reversed, and even how to enter protest words in the game "as they are logging and ranking even incorrect words."

This last thread is pointless as the New York Times does not log the entries, and players cannot enter the proposed protest as they are not recognised words. Yet it is indicative of the sentiment**.

We tell ourselves that free and inquisitive journalism will counter echo chambers. Yet the Wordle example is less convincing in this regard. Like the articles at the start of this piece, online stories significantly reflect the echo chamber more than counter it.

Even when people pointed out the freely visible answers, articles continue to question the data.

"Ruining my day again... Some people believe double-letter words have appeared more frequently in the game since it was acquired by NYT and have accused the publication of adding them."

Even credible newspapers portray any counter-narrative as in the minority, openly questioned, or represented as an outside source. A typical example is, "if you believe one computer scientist, Wordle has not changed."

We now see people with an existing mistrust of The New York Times use this opportunity to reinforce and share their beliefs. Comments in articles reference other issues related to The New York Times or broader assumptions, such as "You can never trust the NYT" or "Of course, they changed it. It’s what they do".

This narrative expansion interlocks the Wordle story with other stories. If a reader believes that Worlde was changed, then it is plausible that other alleged cases must also be authentic, regardless of how fanciful.

It's just a game, so why does this matter for information warfare?

We see a few worrying trends in this simple story about a game. Verifiable facts and data are not trusted online. Questions are asked about data, the informed expert is placed in a minority, or shown as coming from outside the target audience and so cannot be trusted. An online narrative is repeated, often by the organisations that we trust to counter or test those narratives.

The dominant narrative is often the first to gain traction online. Countering that narrative requires more than shooting it down with truth and facts or even people who are specialists. In some cases, knowing about the subject appears significantly more negative when countering the narrative. Readers are unlikely to follow a link and examine the answers within the code (the link is below) and instead continue to believe their preferred narrative.

The TV advert staple of a scientist in a white coat providing data is now actively mistrusted.

We learn from this example to tell a story rather than quote evidence and that merely sharing data is insufficient. Any data must be wrapped into the current narrative and shape a future one. Publishing data about deaths will not change opinion if the audience does not believe the story about the cause of death. It is probably better to use a report that does not directly confront your subject's prejudices before comparing the two cases to avoid instant rejection.

Ideally, the dominant narrative is based on truth, facts, and data, and is adopted because it is both factual and compelling. Sometimes, this will win the information war, yet it is rare to see such a juxtaposition of truth, narrative and data.

The Ukrainian Government's current online narrative is compelling for these very reasons. They have an emotional story, expert opinion and personal witness, with clear evidence to support their campaign. It is a true story.

In contrast, the Wordle stories are regularly false yet compelling, playing to our prejudices and fears and countering evidence with further tales. Their purpose is unclear or genuinely malicious, and they become dominant with sufficient repetition by individuals and trusted organisations.

Wordle may be a game involving five-letter words invented by one person as a game for their partner. It also tells us how we use words rather than data to change our beliefs and that even simple stories are now regularly used to divide rather than unite us together.

Reference

*For reference, the latest version of the code, and all the answers, are here (WARNING this link may give you all the answers to Wordle): https://www.nytimes.com/games/wordle/main.4d41d2be.js

**Although some readers may read this last statement and still subconsciously be saying, "You only say that they do not log entries, but do they?

Is Wordle getting harder? You're not alone if you feel that way (nj.com)

Wordle Is Now Owned by the New York Times (gizmodo.com)

What in the world is happening to our beloved Wordle? | Puzzle games | The Guardian

How Wordle won over the world (telegraph.co.uk)

'Ruining my day again': Wordle 252 frustrates players (yahoo.com)

Embedding sustainability at the heart of MOD operations

With its imperative for a military edge, the MOD is continually focused on driving innovation and military advantage into its operations. A similar focus is starting to apply to climate concerns

With its imperative for a military edge, the MOD is continually focused on driving innovation and military advantage into its operations. A similar focus is starting to apply to climate concerns. Both Defence and climate protection represent true public goods: they are non-excludable and non-rivalrous to the population; we all have it or none of us does. MOD recognises that sustainability and climate concerns are increasingly within its mode of operations.

With its significant financial expenditure, the MOD has considerable responsibility and an excellent opportunity to drive the sustainability agenda, enhancing inter-generational equity and stewardship. Yet, it must do this while meeting defined levels of equipment and platform readiness without compromising capability and recognising, in many places, its over-heated budgets.

Start as a 'fast follower' to then become a 'trail blazer'

The MOD has traditionally sought to lead on implementing innovative ideas, and it has also adapted tried and tested innovations from industries that are not historically defence-focused. This approach of broadening the scope and reapplying technologies can lead to sustainability improvements.

Take the Space industry; for decades, it has utilised solar panels. The MOD employs this same technology as a 'fast follower' by reapplying solar-powered technology for defence purposes. Realising the benefits and capitalising on critical learnings, MOD can bring this development back in-house and become a 'trail blazer' to explore similar technologies applicable in the specific defence context for its own use or export.

With the recent establishment of Space Command, the UK MOD now has the ability to direct this development and agenda. And it can do this using a host of technologies that have been proven elsewhere.

It will be essential to find a balance between in-house initiatives that drive sustainability and new contracting mechanisms that deliver better results through others. A focus on rapid product development, category management, and better collaboration with industry when contracting for outcomes are essential. In all cases, the goal should nurture and retain scarce skillsets with effective partnering.

Shape the supply chain to be more sustainable

In terms of scale and time, the MOD has the largest and longest delivery programmes in government. MOD will finalise financial budgets and delivery plans today for equipment programmes delivered, deployed and utilised beyond the 2040s.

Defence programmes can be among the most pollutant, accounting for 50 per cent of UK central government's emissions. These programmes are economically important too, supporting 260,000 supply chain jobs in the UK. This places UK 2050 Net Zero goals well within the planning horizon in defence procurement and proposed government measures, including mandating suppliers to implement carbon reduction plans, cannot be ignored.

The government has recognised the acute scarcity of natural resources and Defence's massive drag due to the size and longevity of its programmes. The government wants to be firmly in the front seat of the solution when it comes to sustainability.

There is a role for MOD to play in shaping the supply chain through stronger category management approaches, closer long-term partnering with the supply chain on technology investment and adoption, and industrial strategy. This includes the MOD working closely with other departments, such as Business Energy & Industrial Strategy (BEIS) and Home Office, where there is commonality around energy and the manufacturing base needed to support Defence procurement.

Supporting UK industry for global impact

The MOD should leverage its natural clusters in the UK to consolidate supply chains and develop home-grown industries around these critical locations. This localisation could yield far-reaching benefits by creating jobs and reducing carbon emissions by requiring less need for long-distance transport.

In the period 2017-2018, the MOD achieved a 10 per cent reduction in fuel consumption – equivalent to 74 million litres of fuel consumed. This roughly equates to the average family car being able to drive 638 million miles. The MOD could also mandate greater renewable energy as a fuel source with relevant and appropriate procurements.

Defence needs a technology advantage to gain visibility of its entire supply chain, beyond just the immediate suppliers, and develop a more complete understanding of the environmental impact of its equipment programme. This can help MOD and industry to influence the behaviour of sub-tier suppliers with respect to sustainability policies.

Tackle these problems collectively

On the other hand, participating in multi-national procurement and manufacturing opportunities, where appropriate, is another way to achieve environmental improvements. The NATO alliances could provide commonality and modularity across components, systems, and platforms throughout the defence community. Incorporating a build once, use many approach could help cut R&D and recurring manufacturing costs and reduce duplication.

The proposals above won't resolve all of the MOD's sustainability challenges but could provide decisive steps in the right direction. The MOD is trying to balance multiple problems that range from the existential, such as constantly changing Defence threats, to the financial, such as over-heated budgets, to the logistical, a diverse and costly portfolio of assets ranging from light weapons to ships and submarines to procure and support. Amongst all these, it can adopt a more assertive approach to the pressing sustainability challenge.

Warfare in the Intelligent Age

The Intelligent Age has replaced the Information Age. Most military leaders are still struggling with information age thinking and most of their plans will not deliver for at least five years.

Midjourney prompt: Warfare in information

The Intelligent Age has replaced the Information Age. Most military leaders are still struggling with information age thinking and most of their plans will not deliver for at least five years.

Therefore, four changes are needed to accelerate and adapt a military organisation to win in the Intelligent Age:

enhanced leadership that focuses on faster decisions;

prioritised automation of most routine human activities, so that humans can focus on more valuable cognitive and creative tasks;

recognition that more power exists outside defence than within, and that militaries need to adapt, adopt and operate outside their traditional organisations;

transform procurement first to meet military aspirations.

The Information Age was characterised by open and rapid data-sharing; social media-driven utilisation of personal data, often for advertising; and integration of knowledge systems. Information became the new oil, according to one truism of the times. Today, militaries are struggling to adopt and adapt these characteristics even as they are now becoming outdated.

The Intelligent Age is characterised by the Age of With, where every human works with intelligent machines in every activity. It merges the digital, physical and human worlds, collaborating across the boundaries of each to improve performance and empower smarter humans to achieve more at incredible speed.

This accelerated intelligent enhancement threatens to disrupt adoption of information age thinking and to derail preparations for the future. This provides both a military threat yet also an opportunity to disturb slower-moving adversaries by adopting four changes:

Leadership, but better

Leadership will remain critical for military effectiveness in the intelligent age, and ‘intelligent-enhanced’ leadership will prove even more decisive and emphatic by performing better than humans. Age of With leadership constructs acceptable solutions faster than its adversaries, who struggle to collate and comprehend the flood of information ‘oil’ across their processes. Improving decision-making with intelligent abilities will increase the probability of positive outcomes, confer advantage, and enhance military effect.

Automation where it delivers

Good leadership understands that humans are too expensive and valuable to waste on the mundane. The mindset of starting with what can be automated and building upwards must fundamentally change to one that starts with what humans must do and automating everything else. Intelligent systems are better suited to replace routine activities. Highly trained and scarce military humans need to prioritise activities that can only they can do.

Intelligent age militaries must avoid the costly pitfall of sequentially automating individual activities and processes and instead automate functions and roles at a massive scale—including entire staff branches who can be freed for more valuable duties. Those that harness the tremendous growth of automation will be the ones to gain the most significant advantages over adversaries.

Growth will also be faster and cheaper than equivalent step-change through process automation as leaders improve their critical issues by saving time, cost, and effort. A recent British Army empowerment study showed that infantry soldiers spent less than 20 per cent of their time on infantry skills, and that leaders struggling to cope with the routine present had little time to anticipate and prepare for the future.

More power outside than in

Warfare in the intelligent age recognises that, like all modern structures, there is more power outside the organisation than within it. The hierarchical command and relatively insular nature of militaries can combine falsely to reassure leaders that their team is the centre of the universe. Think of the archetypes epitomising military resilience: a battered ship at sea, a fort surrounded by enemies, or a lonely bomber heading home. These all place the military at the heart of the action.

Yet, intelligent age warfare is genuinely unrestricted, integrating national and political strategies across all aspects of a society, including financial, political, and cultural. It does not adhere to what has traditionally been seen as military domains, or deploy only traditional instruments of power. Its boundaryless nature uses intelligent systems to exploit the world outside defence domains, combining influence and power across a society’s agencies and organisations. Intelligent age military power therefore achieves its more limited objectives by using unrestricted measures across multiple vectors, such as media and the economy.

A modern military in this environment will attempt to impose their actions upon an adversary that is dynamically changing within a situation that is rapidly evolving. Enhanced leaders will need to act at increased speed, cycling faster through choices and decisions, and demanding new and original options with possible effects. Victory will depend on human ingenuity to deliver and enhance adaptation and exploitation in minutes and seconds.

Procurement transformation first

Therefore, the final, critical characteristic of enhanced warfare requires improvements to equipment and capabilities that go far beyond software enabling military platforms. Defence procurement organisations and functions must do far more than purchase technology such as AI, robotics, drones, or software for the parts on the battlefield. Every human activity in the Age of With needs enhancement and the procurement function of an intelligent age military must be the first to adopt and implement this transformation.

Without this procurement transformation, all subsequent changes will fail. Military procurement has for too long been measured by what rather than how it buys. Now, it must embrace warfare in the Intelligent Age. The function needs to adopt the mindset of ‘what must be done by humans and automate the rest.’

This will require the same aspirations that the battlefield forces must have to equip the military: use Intelligent Age approaches and methods at scale across their entire organisations. The first and most critical change will be to halt stagnant processes that plan and deliver in years and decades.

Intelligent Age Warfare enhances human insight with intelligent systems that blend physical, digital and human worlds. A successful military will enhance its decision making, improve its leadership performance, exploit power from outside the military, and apply new procurement processes to maintain these changes.

The end of the intelligent age is already foreseeable with the arrival of the quantum age. This will bring into starker contrast the immense gaps between information age and intelligent age warfare. If information was the new oil and intelligent systems the new car, quantum is the new internet. The application of quantum processing and insight will enable an intelligent age military to significantly surpass current levels of effectiveness.

Replacing the Afghanistan Lightning Rod

Afghanistan was a lightning rod that created a local storm

It is hard to easily discuss sacrifice, loss, worth, and purpose, especially in current times when all of these issues feel so raw. I wrote this piece to reconcile my own emotions and to put into context experiences that shaped my life. It is challenging to express this all in 1000 words. I hope, as a reader, that you can forgive and still discuss parts with which you may disagree.

We put a lightning rod in Afghanistan, and for twenty years, it created a costly but localised storm. We may look back, though, and think that it was a period of relative peace and calm.

In 2001, less than 30 days after 9/11, the US military and allies attacked Afghanistan in Operation Enduring Freedom. The subsequent conflict is well documented and hotly debated with the recent withdrawal and Taliban seizure of power.

Afghanistan faces an uncertain and dark future, especially if it returns to the extremist state from before 2001. That return looks highly likely, although not inevitable.

For Afghans, wracked by conflict for decades, it is a return to instability and fear. The period of democracy is over, with Western investment and support for the country abruptly ended.

Right now, there are questions of worth and value for Western armies, who sacrificed their soldiers to maintain that democracy and expenditure. Why did so many soldiers die only to see a return to the same state after 20 years? Why did Western nation-building fail so badly and end in a bitter defeat?

A regional perspective may provide some consolation and, sadly, significant future concerns.

Operation Enduring Freedom was a retaliation to prevent safely harboured Al-Qaeda terrorists from launching similar devasting attacks on the West, especially on US soil and harshly experience on 9/11. The operation achieved this goal, as the US defeated the Taliban state and removed security for Al-Qaeda.

The conflict that followed was bitter, costly, and unforgiving, yet restricted to the fields and mountains of Afghanistan. The US hounded Al-Qaeda across borders, and the Taliban resisted where they could. Islamic extremists congregated and died around the Western lightning rod in Afghanistan. There were significant losses on all sides, yet there was no repeat of 9/11 elsewhere. Extremist attacks took place but without coordination.

The US-led presence also focussed regional attention, creating a focus for nations that restricted their freedom of manoeuvre.

West of Afghanistan, Iran faced a US military presence on both sides, and US aircraft could reach Tehran from East or West. This split threat forced Iran to divert forces from its predominant zone of influence in the Gulf and disperse air defence assets countrywide. In extremes, a US attack into Iran would be slightly easier from Afghanistan, as it would avoid the Zagros Mountains that protect Iran's western flank.

In the south, Pakistan maintained an uneasy relationship with the US government and military. Accused of harbouring Al-Qaeda, military operations from Afghanistan into Pakistan were a constant issue. Most notably, Operation Neptune Spear launched into Pakistan to kill Osama Bin Laden without informing the Pakistan government.